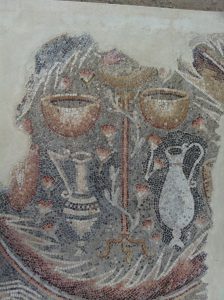

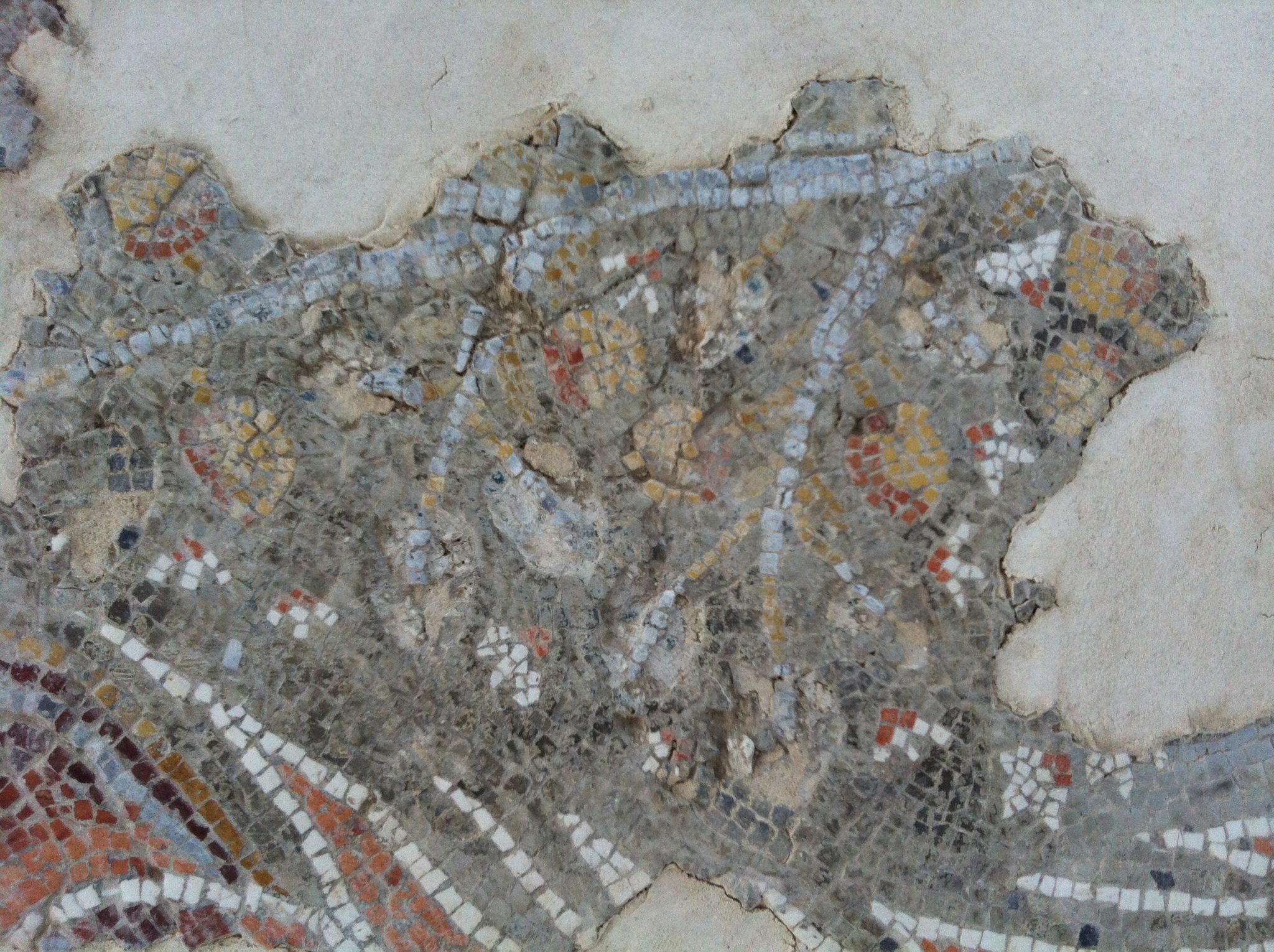

Sheaf of wheat and grain, mosaic from the Samaritan Synagogue of Samaria, photo: Dr. Anat Avitalאלומת חיטים ודגן, פסיפס בית כנסת שומרוני סמארה, צילום: ד"ר ענת אביטל

The central hall of the Samaritan synagogue in Samara features a remarkable mosaic, made with tiny, colorful tesserae stones, which give the image high resolution and allow for detailed depictions of agricultural produce.

Creating this mosaic required substantial financial investment and skilled artists who closely observed local crops and farming practices.

The elaborate decoration highlights the synagogue's significance, the wealth of its patrons, and the central role of agriculture in the Byzantine period, symbolizing its connection to divine blessing.

This fascinating artwork offers a unique glimpse into the culture and values of the time, making it a must-read for those interested in ancient art and history.

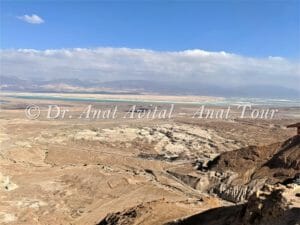

Museum of the Good Samaritan and the Samara Mosaic

Avital, A. (2015). The Originality of the Unique Agricultural Depictions in the Samaritan Synagogue Mosaic at Samara. Studies in Judea and Samaria, 24, 145-163. Ariel University Press.

The article has been translated from Hebrew into English with the assistance of the Gemini language model

Originality of the Unique Agricultural Depictions in the Samaritan Synagogue Mosaic in Samara

Anat Avital*

The central hall of the Samaritan synagogue in Samara is paved with an original and impressively beautiful mosaic. The exceptional quality of the mosaic was achieved through the use of very small, colorful tesserae stones, which provide the image with a high resolution, allowing the presentation of numerous and original details related to agricultural produce. Financing the creation required a significant financial investment, and the project's execution necessitated the employment of exceptionally talented and creative artists who observed the local crops and agricultural routines. The immense investment in decorating the synagogue with diverse agricultural items indicates the importance of the synagogue in Samara, the prosperous economy of the synagogue's patrons, and the place of agriculture in the Byzantine period as a central value for human existence and its connection to divine blessing.

This article is part of the results of a comprehensive study aimed at identifying and analyzing the appearances of crops and agricultural tools in the mosaics of the Land of Israel. For the research in question, the Byzantine mosaics currently known to us from the Land of Israel were re-examined, and the agricultural crops appearing in them were thoroughly inspected both through direct observation and through new close-up photographs at sites accessible for photography. The quality of the mosaics was measured by the number of stones per square decimeter (dm²), and after a meticulous examination of 125 measurable and evaluable mosaics, a scale was established based on an average density of 120 stones per dm². To create a normal distribution that would provide a scale for the quality of the mosaics of the Land of Israel, a quality scale was established from 1 (low) to 3 (high): 1 – up to 100 stones per dm²; 2 – 100–130 stones per dm²; 3 – over 130 stones per dm². According to this rating, the rare density of the stones in the Samara mosaic, which stands at 400 stones per dm², is among the highest in the mosaics of the Land of Israel, reaching a level only slightly lower than the maximum stone density in the Land of Israel, 450–500 stones per dm², achieved in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. The research also revealed that the average number of crops depicted on mosaics from the fourth century CE is only 3.5 species per single mosaic, while in the Samaritan synagogue mosaic of Samara, it is 11 different crops, meaning the number of crops presented in it is 3.1 times the average in contemporary mosaics (Avital, 2014).

Mosaic Painting – Technical Background

The first mosaic creations were installed in Greece during the Hellenistic period and were composed of pebbles in shades of black, white, and sometimes red (terracotta fragments) in an attempt to create a substitute for painting. In the third century BCE, the Greeks began to create tesserae stones from pebbles cut into square stones, and in the second century BCE, the renowned colorful mosaic floor 'Asarotos œcos' from Pergamon was laid (Dunbabin, 1999, pp. 1–27). The art of mosaic entered Italy in the first century BCE with the laying of the 'Nile Mosaic' in the Temple of Fortuna in Praeneste (= Palestrina) (Pliny, XXXVI, 60, 64), and by the end of the first century BCE, colorful and high-quality mosaic floors were already being installed in the Land of Israel.

Mosaic painting is a technique of depiction using clusters of square and colorful stones that together create a complete image. Each stone represents a pixel in the image, and together the stones compose a meaningful colorful image, similar to the pixels that create the grid of a digital image. Usually, the resolution was not particularly high because the size of the stones was limited to the budget available to the artists to execute the creation, and the size of the tesserae stones generally ranged from 4 mm² to 1.1 cm². Only rarely (and not in the mosaics of the Land of Israel) did the budget allow the use of tiny stones (4-9 mm²) to cover a large area (e.g., the 'Nile Mosaic' from Palestrina and the 'Alexander Mosaic' from Pompeii). In Israel, stones of this size are extremely rare, and they were used only to fill small corners and to provide accuracy in eye depictions.

Considering the fact that the mosaic is laid on the floor, the viewer standing on it must understand the message from their standing distance, meaning they must be able to decipher the image from a distance of about one and a half to two and a half meters. Therefore, when small stones were used, a sharp, clear, and detailed image was obtained, and at the same time, it was possible to reduce the size of the depicted elements, so that the viewer could stand right on the motif and perceive it in its entirety (the scenes from the Dionysus House mosaic in Zippori, for example, are suitable for deciphering even from a sitting distance). The viewers' distance from the decoration was a constant, and therefore it was not possible to greatly enlarge the motifs. It is self-evident that in cases where large stones were used, an image with a low resolution was created relative to the given area.

As is known, anyone standing at the entrance to a hall covered with a mosaic cannot grasp all the details from their standing position, and they must move across the "carpet" and examine the items one by one. To make it easier for the viewer, large carpets were divided into separate panels, so that they could decipher the scenes and the separate decorations from a standing distance and close to them. The composition of a large and detailed mosaic also required special artistic skills from the artists in terms of overall visual perception of illustration in a large space. Despite the enormous objective challenges facing the artists, it seems they overcame them, and one can certainly admire their success. The message conveyed through the mosaics is understandable and impressive, and even today we can understand most of its content and learn from it about the perceptions and views of the ancients.

The range of colors of the tesserae stones that composed the floors ranged from minimal; black and white, to a range of 20 colors and many intermediate shades (Avi-Yonah, 1934b). The hard and white limestone from the Cenomanian and Turonian periods is very common in the Land of Israel, and therefore it was used to create the background of most floors in Israel. The colors yellow, orange, mustard, brown, and red were also obtained from shades of the local hard limestone. Red and orange were sometimes also produced from terracotta. Black, gray, and greenish-gray were produced from other minerals found in the rocks of the Land of Israel from the Senonian period. Additional colors, such as blue, light blue, green, turquoise, and purple, were produced from minerals not found in the Land of Israel and had to be imported. Smalti glass tiles and obsidian (volcanic glass) were used in low proportions to emphasize delicate and unique parts of the mosaics, such as eyes, delicate branches, and jewelry (Avi-Yonah, 1962, pp. 63–70; Sukenik, 1929, pp. 111–117; Sukenik, 1932, pp. 20–39, Plates VIII–XXVII; Foerster, 1985, pp. 383–385; Pliny, XXXVI, 67). The conspicuous lack of green-colored rocks in the Land of Israel deserves special mention here because its absence dictated the use of stones of alternative colors to depict green plant parts. Thus, leaves and stems or fruits with green peels were presented using stones of various colors. However, despite the absence of the color green, the plant parts depicted in the mosaics are always identifiable as plant parts.

The numerous figurative motifs designed using mosaic paintings reveal individual character and design, and it is evident that the selection of elements in each mosaic was done locally. Although at first glance the products appear similar in their subjects and the composition of the carpet, after careful examination, a world of original and independent designs is revealed in each mosaic. Some believe that the mosaic artists used pattern books, but even if the artists used such pattern books, they demonstrated in each creation a renewed planning of the composition and an independent design of the figurative patterns (Hachlili, 1987; Avi-Yonah, 1934b, p. 62; Blanchard-Lemee, et al., 1995, pp. 10–15; Dunbabin, 1999, pp. 303–304; Hachlili, 2009, pp. 145–147, 175, 273; Talgam, 2002, p. 71, note 71; Weiss, 2005, p. 124; Hachlili, 2009, p. 155). In contrast to the original figurative designs, geometric patterns or plant tendrils that create frames and medallions or fill spaces were also designed. These patterns are repeated and replicated similarly in many mosaics, and it is very likely that pattern books that were passed between the artists and from site to site were indeed used for their design.

The Accuracy in the Design of Realistic Details

The accuracy in the design of realistic details in the art of the period indicates a deep observation of nature. Evidence of this is already apparent in early Roman art (Caneva, et al., 2014) and later in the mosaics of the late Roman and Byzantine periods (Tzaferis, 1983, pp. 23–25; Trilling, 1989, pp. 56–59; Blanchard-Lemee, et al., 1995, p. 169; Dunbabin, 1999, p. 298; Weiss, 2005, p. 124; Hachlili, 2009, p. 155). Therefore, in recent decades, a research approach has been developing that attributes great importance to the data emerging from the mosaics as a historical document (Bowersock, 2006), and they serve as a medium reflecting the life of the period (Ovadiah, 1991, pp. 7–13), similar to photos in travel diaries or social networks today. By combining data from contemporary writings, one can learn from these decorations about the economy, agriculture, and food development, society, culture, and religion in ancient times (Dalby, 2003, pp. viii–xvi; Janick, et al., 2007, pp. 1452–1453; Avital, & Paris, 2014).

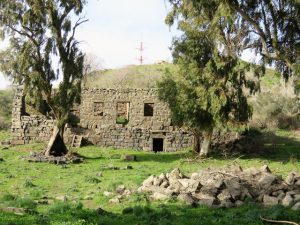

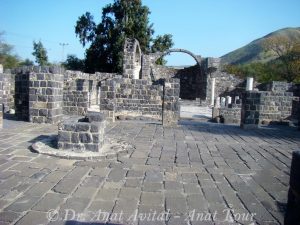

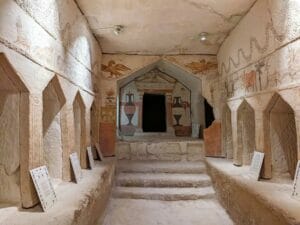

The Samara Synagogue Mosaic

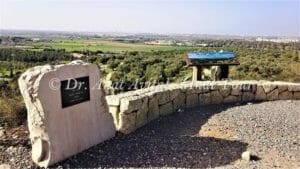

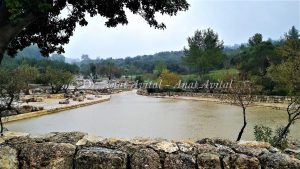

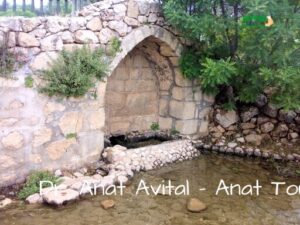

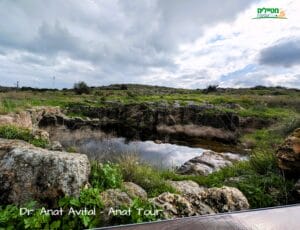

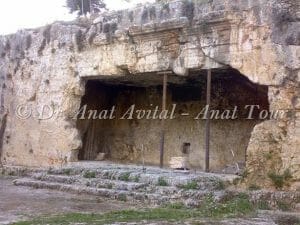

The Samara synagogue is located nine kilometers east of Taybeh, near the settlement of Einav (coordinates 1609.1872). The mosaic of the central hall of the synagogue is dated to the fourth century CE, and its internal dimensions are 15 meters in length and 8.4 meters in width (126 m²). The central carpet of the synagogue is divided into two squares surrounded by frames of acanthus leaf medallions populated with depictions of agricultural crops, tools, and objects (Magen, 2008, pp. 142–167). The medallions in the northern row are populated with an almond-bearing branch, wheat sheaves, vine tendrils modeled on a tripod, a pomegranate-bearing branch, olive branches, sycamore figs on a branch, a jug pouring red wine into a saucer, and red rose-bearing branches around it. The middle row of medallions between the two square carpets is populated with a date palm spathe, date palm trees, and a sickle for harvesting. The medallions in the southern row are populated with an apricot-bearing branch, a peach-bearing branch, and a stone pine branch bearing cones.

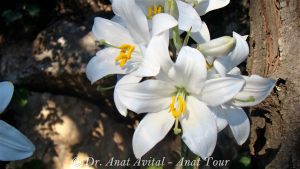

Almond Branch (Amygdalus communis L.)

The almond branch is designed with light bluish stones. The leaves are designed with turquoise stones (most of which have been destroyed), and they have veins of the same light bluish stones. The branch bears bicolor fruits of reddish-brown and orange stones, representing the fruits of the previous year. At the tips of the branches, tiny white flowers are visible, and the flower's calyx is designed with reddish stones (Figure 1). The realistic image obtained accurately depicts the branches of the almond tree ("shkedia") at the peak of the winter season, when the branches simultaneously bear both winter flowers with reddish calyx leaves (Figure 2) and brown fruits from the previous summer that remained on the tree alongside the fresh bloom (Figure 3). The almond tree is decorated in a total of five mosaics from the Land of Israel by presenting an entire tree, a branch, or a single fruit. An almond tree bearing leaves and fruits is decorated in the Deir Qala Church (Hirschfeld, 2003), and there too, it is possible that reddish fruits from the current year are depicted at the tips of the branches, alongside mustard-colored fruits from the previous year, located in the inner part of the branches. It seems that this decoration in the Samara synagogue was created about a hundred years earlier and was inspired by the same description or an even earlier one located not far from Samara. An almond branch bearing leaves but no fruits is presented in the Hamat Tiberias synagogue (Dothan, 1968) adjacent to the figure of the autumn season. A single fruit of an almond appears once in the Zippori synagogue adjacent to the figure of the autumn season (Weiss, 2005). Apparently, in mosaics from across the empire, no depiction of the almond tree or its branches can be pointed out at all, but a single design of the almond fruit is seen on the "Unswept Floor" mosaic, which may indicate independent and original creations from the Land of Israel. Moreover, the original decoration of almond trees in the mosaics of the Land of Israel can indicate the great importance of the tree from a local economic point of view compared to its lesser importance, apparently, in other countries. The almond is among the first trees to be domesticated for agriculture already in the Chalcolithic period. Initially, the almond was transferred to the Near East region and introduced into agriculture, from there the tree spread to all the countries of the Mediterranean basin (Hyams, 1971, pp. 30–31; Zohary, Hopf, & Weiss, 2012, pp. 147–149). The almond is mentioned in the Bible, and in rabbinic literature, it is mentioned in a variety of halakhic topics (Felix, 1967, pp. 102–103; Felix, 1994, pp. 143–148). Roman writers described the bitterness of the almond fruits, their nutritional value, and ways to sweeten them, and passed on instructions for growing the tree (Varro, I, 6, 1; Columella, V, x, p. 249; XI, ii, pp. 462, 483; Pliny, XV, 12; XVII, 43; Galen, 29, 612, pp. 93–94).

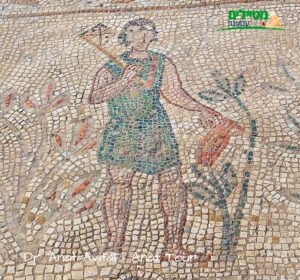

Two Sheaves of Wheat (Triticum)

Two sheaves of wheat, each binding five ears, are wrapped in a striped ribbon or stalks. To the right of the sheaf is a red rose flower, identical to the roses adjacent to the wine-pouring jug described below (Figure 4). The ear is composed of two rows of large grains with long awns at their tips, accurately simulating wheat ears. The upright design of the wheat heads after ripening reinforces the image of wheat, in contrast to the appearance of barley ears, which bend their heads downward during ripening, and the drooping stalk creates an inverted U shape. The great importance of wheat as human food and its nutritional advantage over barley also reinforce the identification, as stated in Mishna Torah by Maimonides: "Whatever is designated for human food, such as wheat…" and in the Jerusalem Talmud: "For seeds, barley… food for beasts…" (Pesachim 82, 5, 12, 72b).

Wheat Sheaves (Triticum)

Despite the well-known importance of wheat to human sustenance (Safrai, 2010), sheaves are presented in only five other mosaics from the Land of Israel. There, they symbolize harvest time in the summer season, and they are not displayed as prominently as in the Samara mosaic. Wheat was not used as a motif displayed for show in the mosaics of the period, probably because wheat is not a juicy fruit served for eating like other fruits, and because wheat has no economic value to humans without grinding and baking. Sheaves are depicted in the hands of figures representing the summer season or adjacent to them in mosaics from the Lady Mary Monastery in Beit She'an (FitzGerald, 1931), from the Villa of El-Maqarqash (Vincent, 1922), and from the Jewish synagogues in Zippori, Usfia (Avi-Yonah, 1934a), and Hamat Tiberias. In other mosaics from the Byzantine period outside the Land of Israel, sheaves of wheat are also seen, usually in a clear context of depicting the summer season and harvest time, for example, in eastern Transjordan (Piccirillo, 1993, p. 60, Fig. 13), in Antioch (Cimok, 2000, pp. 134–143, 211), in North Africa (Blanchard-Lemee, et al., 1995, p. 18), and in Greece (Akerstroem-Hougen, 1974, Fig. 75, 3). The original depiction of two wheat sheaves from the Samaritan synagogue in Samara, in a context of display and decoration without a seasonal context, is unique and indicates a local creation that probably reflects the pride of the building's patrons in local agriculture.

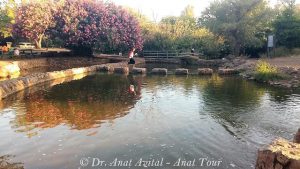

Vine Tendrils on a Trellis (Vitis vinifera)

Vine tendrils bearing rounded red grape clusters are entwined and modeled using tendrils on three yellowish stakes forming a trellis (Figure 5). This trellising technique on poles forming a trellis has been preserved to this day in traditional villages in Samaria and Mount Hebron (Figure 6). As is known, the vine was one of the most important agricultural branches in the ancient economy of the Land of Israel (Safrai, 2010; for further reading, see Felix, 1968). Therefore, and also because of the vine's visual beauty, it became the most common agricultural branch among all the branches represented in the mosaics of the Land of Israel, and it is decorated on 104 mosaics, which is 83% of all the mosaics in which agricultural produce is presented. Despite the prevalence of vine decoration, this depiction of vine trellising on a trellis is the only one depicting trellising in the mosaics of the Land of Israel. The trellising operation was intended to support the vine bushes and raise them above ground level using auxiliary means. Without this support, the vine sprawls on the ground and spreads into space due to the weakness of the trunk and branches. In ancient times, several methods of trellising vines were practiced, and some of them have been preserved in traditional villages to this day. In the past, vines were planted close to tall and strong trees, and the vine would entwine around the tree and climb it using tendrils (Columella, II, p. 127; Pliny, XIV, 3; Cato, pp. 19, 6, 4). This trellising method is reflected in a mosaic from the Bostra Tower, Deir el-Adas, Syria (Balty, 1977, p. 148). Trellising of a vine on a pergola that stretches over workers is presented in a mosaic from Algeria (Dunbabin, 1999, p. 119) and in the agricultural calendar mosaic from Saint-Romain-en-Gal, France (Lafaye, 1892, p. 341; Stern, 1981, p. 447, Pl. XIX 50). The construction of such pergolas for trellising vines is still practiced today in traditional villages in the Land of Israel and elsewhere. Single depictions of vine trellising on trees or pergolas were presented in mosaics outside the Land of Israel, but vine trellising on a trellis was depicted only once, in the Samara mosaic.

Pomegranate Fruits (Punica granatum)

Reddish pomegranate fruits are presented on a branch. The pomegranates have a prominent crown, and their center is light to emphasize the fruit's shine in a stylized design (Figure 7). The pomegranate is the second most common crop in the mosaics of the Land of Israel. It is designed in a variety of ways in 50 mosaics, which is 37% of all the mosaics in which agricultural produce is presented. Pomegranates are presented in small groups filling spaces between acanthus leaf medallions and a single pomegranate in a geometric medallion, for example, in the Beit Loya Church (Patrich, & Tsafrir, 1993). Pomegranates are presented in pairs or small groups, sometimes slightly stylized, and populate geometric medallions, for example, in the Orpheus Chapel from Jerusalem (Vincent, 1901). Sometimes the pomegranates are seen on a tree that fills the entire medallion, for example, in the Bethlehem of Galilee Church (Oshri, 1996). Rarely is a stylized and highly realistic decoration of a pomegranate tree seen, for example, in the Kissufim Church (Cohen, 1980), and sometimes the pomegranates are placed in baskets, for example, in the Feast House and the Nile House in Zippori (Weiss, 2002) and in Ma'on-Nirim (Avi-Yonah, 1960). In the art of mosaics outside the Land of Israel, the pomegranate also has a presence as a tree depicting an open agricultural landscape, and its fruits are displayed for show or presented as an offering in baskets, for example, in the Church of the Virgin Mary, Madaba (Piccirillo, 1993, p. 54, Fig. 6). The significant frequency of the pomegranate in mosaic decorations corresponds to its many mentions in the literature of ancient times. The pomegranate is mentioned many times in the Bible and in rabbinic literature in a variety of halakhic, agricultural, and industrial topics, as well as in Greek and Roman literature (Theophrastus I, iii, 3–5; II, ii, 2–6; IV, xiv, 9–10; Varro I, 41, p. 273; Columella, XXIII. i-ii; Pliny XV, 18; XVII, 21–45; XXII, 43; Celsus, II, 24; Galen I, pp. 89–91).

Olive Branches (Olea europaea)

The tips of olive branches are designed in a mostly destroyed medallion (Figure 8). The elongated opposite leaves, divided into two different colors along their length: black and gray, are suitable for describing olives, but since the lower part of the branches has been destroyed, it is impossible to know if olives were originally decorated on the branches as well. In the mosaics of the Land of Israel, only one more olive branch bearing fruit is seen in a decorative context in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (Richmond, 1936), and two olive tree branches without fruit in a decorative context in the Beit Anon Church (Magen, 1992). Designs of olive trees are completely absent from pastoral descriptions depicting open agricultural landscapes or orchard areas, both in the Land of Israel and elsewhere. Compared to the great and well-known economic importance of the olive (Safrai, 2010; for further reading, see Felix, 1991, pp. 97–112), its low number of appearances on mosaics is surprising. It is possible that the reason for the absence of olive branches from the decorations is that the main importance of the olive tree is concentrated in its oil, which was used for food, lighting, body anointing, healing, and industry, and not in the tree's branches, whose economic importance was less. One could have expected, therefore, a display of oil jugs, but they are also absent from the mosaic decorations. In contrast to the absence of the olive tree with its fruits from the mosaics, other trees bearing large, colorful, and prominent fruits are seen in abundance in many mosaics, and it appears that the descriptions on the mosaics were intended to impress the viewer's eye with large and beautiful fruits in order to praise and glorify the high abilities of the farmers of the period, their agro-technological achievements, and the finest and most colorful produce. Olives do not meet these purposeful visual requirements because they are small, green, and not visually appealing fruits.

Sycamore

A small, bluish-white part that survived from the description of sycamore figs populates a medallion (Figure 9). The reddish figs are varied in orange and pink colors, and they are larger than the yellowish figs. The rounded shape of the fruit, the density of the fruits, their proximity to the branch, and the variety of sizes and colors can indicate the artists' intention to depict a branch of a sycamore bearing figs of different ages; the yellow ones are young, and the reddish ones are mature (Figure 10). It is possible to point with (almost) certainty to the decoration of sycamore fruits in three other mosaics from the Land of Israel, located in climate zones where sycamore trees are able to grow: the Nile Feast House from Zippori in the Lower Galilee, the Beit Loya Church, and the Madras Church in the Judean Shephelah (Ganor et al., 2011). The sycamore is a thermophilic tree, and therefore it was one of the prominent trees on the coastal plain of the Land of Israel after it was artificially brought here by humans. The sycamore was grown for the use of its fruits for food and medicine until the modern period in the mid-20th century. However, sycamore trees were mainly grown for the use of their wood. In the late Roman and Byzantine periods, the sycamore is mentioned as characteristic of the Shephelah region. The sycamore also marked the border between the Lower Galilee, which grows sycamores, and the Upper Galilee, which does not grow sycamores (Galil, 1966; Danin, 1991). The location of Khirbet Samara at an altitude of 370 meters above sea level is suitable for growing thermophilic sycamores, and this description can enrich our knowledge of the variety of agricultural crops that were prevalent in the region. This realistic design of sycamore figs growing on the tree's branches is unique in all the art of the period.

Jug and Roses

A red metal jug is presented horizontally as it pours red wine into a saucer, and nearby are branches bearing red roses (Figure 11). The red grapes are modeled on the trellis mentioned above. Around the jug, rose bushes are entwined, indicating the cultural cultivation of ornamental flowers. Similar roses are also decorated in other medallions and among them. Most of the rose flowers are designed as they grow on a stem in a side view, and some, apparently, are presented in a delicate design in a top view between the date palm trees, next to the date palm spathe and near the cage.

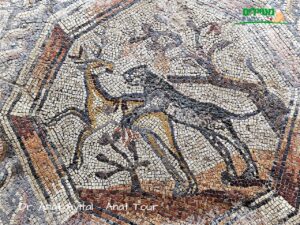

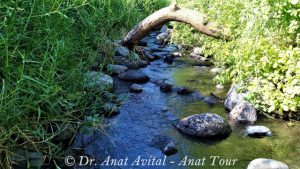

Date Palm fruit branch, Date Palm Trees, and Sickle

In the middle row of medallions between the carpets, a large date palm spathe is populated (Figure 12). The spathe's spadix is designed with reddish stones, and the dates are varied in brown and greenish colors. This is a unique decoration of a large date palm spathe in the mosaics of the Land of Israel. In the mosaic of the Lady Mary Monastery from Beit She'an, a spadix bearing three date fruits in a schematic design is decorated. In a nearby medallion, two tall date palm trees (Phoenix dactylifera) and a hand sickle with a wooden handle and a smooth and curved metal blade are presented (Figure 13). The date palm trees have a striped trunk in brown shades, and their fronds are varied in gray and turquoise stones, most of which have been destroyed. The artists managed to create a proper perspective so that the two date palm trees give the image the appearance of a complete date palm grove. The proximity of the sickle to the date palm trees hints at its use in date harvesting because the presentation of a tool with a hint to the plant, the object of its work, is repeated in other mosaics as well. For example, a hand sickle is presented in the context of harvesting in the synagogues of Zippori, Beit Alpha (Sukenik, 1929), and Usfia. The sickle is presented in the context of harvesting vegetables and picking flowers in the spring season in the Zippori synagogue or in the context of picking citrons in the Kariot Church. Exceptionally in all the art of the period, the sickle is described as a hint to harvesting in the Samara mosaic. The diverse functions of the sickle in cutting various plant parts are mentioned in rabbinic literature and also in Roman literature: harvesting green wild grasses as fodder for animals, cutting branches and tree parts, cutting thorns, cuttings and bushes, picking flowers and fruits, and harvesting grapes (Columella, IV, 7, p. 371; II, 17, p. 209; White, 1967, pp. 85–89).

Date palm trees are presented in only ten mosaics from the Land of Israel, and in each mosaic, they are presented in a different design. The role of the date palm trees is to decorate the mosaic, to symbolize the abilities of the region's farmers, to present the splendor of their produce, and to depict an open rural landscape, for example, in the "Calocaria" mosaic from Caesarea (Israel Antiquities Authority, Caesarea Sands). In schematic and simple designs, the trees sometimes serve as dividers between panels or medallions and fill space (horror vacui), for example, in the Beit Alpha synagogue. Sometimes the spadices with the fruits are incorporated into the landscape of the date palm trees in various ways: in the lower part of the tree landscape in the "Calocaria" mosaic from Caesarea, in the upper part of the tree landscape in the Bethlehem of Galilee Church, or among the date palm fronds in the Samara mosaic under discussion. These descriptions testify to the direct observation of the date palm tree landscapes by the pattern designers, which yielded individual creations. Date palm trees without fruits, perhaps male trees, are also designed in some of the mosaics, and their role is to decorate the mosaic with an impressive tree in its beauty and height, for example, in the Ma'on-Nirim synagogue, or with trees depicting an open rural landscape in the Dionysus House in Zippori (Talgam & Weiss, 2004). The date palm tree rarely appears in mosaics from across the Mediterranean basin. It is very interesting to note that in all its appearances in Italian art, the tree is described without fruits, and on the few occasions that date fruits appear, they are presented in baskets for serving or on a shelf in a kitchen. These testimonies, combined with data from the literature of the period, lead to the assumption that these date fruits were imported from warmer countries where the cultivation of quality fruits was possible (London, 2005, p. 38).

The commercial cultivation of dates in the Land of Israel today is concentrated in very hot places along the Syrian-African Rift, where the average temperature is 30 degrees Celsius. These heat conditions allow the tree to yield high-quality fruit. In ancient times, the tree was grown for its fruits also in the mountainous areas of the country. As a result, the trees yielded inferior fruits and were therefore disqualified for first fruits, as written in the Mishnah: "They do not bring first fruits… from dates from the mountains" (Mishnah, Bikkurim 1:10). The unique combination of the date palm grove, the fruit-laden spathe, and the sickle in one image in the Samara mosaic – which documents realistic details that were designed locally and specifically for this mosaic – can testify to local cultivation that succeeded in yielding quality fruits

Apricot (Prunus armeniaca)

In the southern row of medallions, a branch of an apricot tree is designed using orange and brown stones. The branch bears small, whole leaves made of light bluish stones (Figure 14). On the branches, kidney-shaped apricots are borne. The contour is designed using orange stones, and the colors lighten towards the white fruit center. The shape and orange colors of the fruit indicate that the fruit is an apricot. To the best of my knowledge, apricots can only be identified in three mosaics from the Land of Israel and not elsewhere. Apricots were designed on a branch in a public building in Zippori ("Double Axe") (Talgam & Weiss, 2004) and were incorporated into the tree landscape in the Bird Mosaic Palace in Caesarea (Porath, 2006). In these decorations, the orange color of the fruits is clearly visible. Their kidney-like shape, the visible stem along the fruit, and their alternate growth along the branch correspond to their realistic appearance. The apricot was probably domesticated in northern China or East Asia about 3,000 years ago, and as a domesticated tree, it spread relatively late, in the third century BCE, to the Mediterranean region through Iran or Armenia (Zohary, Hopf, & Weiss, 2012, 144). The apricot is not mentioned in the Bible or in rabbinic literature, but it is mentioned a few times in classical literature (Columella, V, 10, p. 248; Pliny, XV, 12; XVI, 42).

The scarcity of apricot fruit appearances on mosaics corresponds to our knowledge of it being a fruit with limited economic value due to its acidity and rather bland taste, as Galen states (Galen, p. 34, 466). However, the beautiful, ripe, and large fruit designs that grow densely on the branch indicate the high abilities of the region's farmers to grow new and high-quality fruits, and this, apparently, was the pride of the patrons of the work. Original creations for designing branches bearing apricot fruits testify to direct observation of the surrounding nature and local agriculture and reinforce the understanding that mosaic decorations can teach about local reality.

Peach (Prunus persica)

In a nearby medallion, a branch bearing peaches is designed, modeled in the shape of a large drop using a variety of red, brown, and white stones that create shadows and give volume to the fruit. The thick branch at its base splits into sub-branches that become thinner at their tips (Figure 15). On the branches, leaves are designed, delineated by a line of white stones, and the rest of the leaf is made of green glass stones, most of which have been worn away. In the mosaics of the Land of Israel, about 20 more diverse and original descriptions of peaches are presented, indicating the fruit's penetration into local agriculture. It can be inferred that farmers in the Byzantine period had already succeeded in raising the fruit to a worthy level of sweetness and taste instead of its bland taste, which was known in the preceding Roman period. For example, in the Bird Mosaic Palace from Caesarea, peaches were described in their natural state on the tree, in the Church of the Nativity they were presented attached to a stem and displayed individually inside an acanthus medallion, in the Kursi Church (Tzaferis, 1983) they were designed without a stem for serving on a heart-shaped leaf base, and in the Nile Feast House mosaic from Zippori, they are presented for show and as an offering in a basket with other fruits. In mosaics from outside Israel, the peach rarely appears: it is presented, for example, in mosaics in Madaba (Piccirillo, 1993, p. 126, 104). The peach grows wild in the mountains of northern China and eastern Tibet, and it arrived through Iran or Armenia to Greece in the seventh century BCE. The Romans domesticated the tree from the first century CE, and it penetrated the Near East and the Middle East as a cultivated crop (Zohary, Hopf, & Weiss, 2012, pp. 144–145, 172). The peach is not mentioned in the Bible, but it is mentioned by the name "persk" many times in rabbinic sources. This implies that the tree was among the crops of the Land of Israel in the Roman and Byzantine periods (Felix, 1967, pp. 101–103; Felix, 1994, pp. 229–232). Roman writers also knew the peach, and they wrote about its history and properties and provided instructions for growing it (Columella, XI, 2, 462; Pliny, XII).

Stone Pine (Pinus pinea)

A thick branch of the stone pine is designed using purple stones, and thin branches made of light stones branch out from it. On the thin branches, needle-like and thin leaves are borne, made of a single row of green glass stones, most of which have been worn away. Large and ripe cones are also borne on the branches (Figure 16). The cone scales are described accurately and particularly impressively. The scale is surrounded by a frame of brown stones, and its inner part is pink. The point in the center of each scale is described with a single brown stone, and its function is to describe the protrusion on the scale. This is an accurate design of a stone pine branch, evident from the massive structure of the cone, the prominent point in the center of the scales, and the needles arranged like brushes on the branch. Stone pine cones are presented in only five mosaics from the Land of Israel. For example, they are presented above a saucer in a villa in Ein Yael (Wexler-Bdolah, 2007), in an acanthus medallion in the villa mosaic in Shechem (Dauphin, 1979), and in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. These cone descriptions are realistic and faithful to reality, and it is evident that the cone receives a place of honor as a large fruit compared to the other fruits around it.

The stone pine was used in ancient times as an agricultural crop, and its fruits were also used by gathering from the wild. Stone pine seeds were used for food in Greece and Rome due to their high oil content, and its wood had a variety of uses. The stone pine grows wild around the Mediterranean basin in coastal areas on sandy soils (Coombes, 2004, 41). According to researchers, the tree did not grow wild in the Land of Israel (Felix, 1994, pp. 177–178), and they believe that from the Roman period it was grown in the country as a cultivated tree (Kislev, 1988, 46; Felix 2000, 300, note 18). The tree was also mentioned by Roman writers in various contexts: the quality of its seeds for food, wood uses, its uses for ornamental purposes, and the methods of propagating the tree in nurseries (Celsus, 2.24; Columella, IV, 26, p. 429; Varro, I, 6, p. 193; I, 15, p. 29). The unique appearance of the cones specifically in prestigious mosaics in Israel – the Church of the Nativity and Samara – indicates their rarity, the high price of stone pine seeds in the diet of the people of the period, and the special pride of the building's patrons in growing the tree with high-quality wood.

Summary

The Samara mosaic excels in high quality achieved by using exceptionally small colorful stones and a unique and original design of agricultural crops and tools. The high quality of the mosaic indicates a community with means. The original and realistic designs indicate direct observation of local crops. The Samara synagogue mosaic presents 11 different agricultural crops, a number 3.1 times greater than the average number of species presented on a single mosaic from the fourth century, which is 3.5 crops per mosaic. It is interesting to note that the Samara mosaic features traditional species important to human economy in ancient times: vine, grain, olive, date, and almond, alongside tree species that entered cultivation later in the second domestication phase: apricot and peach. To achieve quality fruits, the propagation of these trees depended on sophisticated vegetative propagation techniques, particularly the grafting technique, which greatly improved only at the end of the Roman period and during the Byzantine period. The stone pine also arrived in the region as a cultivated tree only in the Roman period. The descriptions of the sycamore and stone pine represent trees that were grown for food and wood purposes, and they can hint at industrial and construction activity, settlement expansion, and a thriving economy. The common denominator for all the decorations is the combination of several traits and characteristics that allow the crop's entry into the decorative repertoire, as was customary in the mosaics of the period: presenting the finest produce of large, colorful, and prominent fruits and presenting agricultural activity and agro-technological achievements. Since finding food was one of the greatest concerns of humans in ancient times, it can be assumed that the beautiful descriptions from the Samara mosaic were intended to present a rich yield aimed at impressing viewers and drawing them closer to faith in divine protection, which promises a blessed economy for believers.

בטח, הנה רשימת המקורות שסיפקת, מתורגמת לאנגלית ומסודרת כראוי:

Bibliography

- Akerstroem-Hougen, G. (1974). The Calendar and Hunting Mosaics of the Villa of the Falconer in Argos: A Study in Early Byzantine Iconography, Vol. I Text; Vol. II Pls., Stockholm: Svenska institutet i Athen.

- Avital, A. (2014). The Agricultural Crops and Tools in Mosaics from the Late Roman and Byzantine Periods in the Land of Israel. Doctoral dissertation, Bar-Ilan University. (Hebrew)

- Avital, A., & Paris, H. S. (2014). Cucurbits depicted in Byzantine mosaics from Israel, 350-650 CE. AoB, 114(2), 203–222.

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1933). Mosaic Pavements in Palestine. QDAP, II, 136–181.

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1934a). A Sixth-Century Synagogue at 'Isfiya'. QDAP, III, 118–131, Pls. XLIX-LIV.

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1934b). Mosaic Pavements in Palestine. QDAP, III, 26–73, Pls. XIV-XVIII.

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1958). Ten Years of Archaeology in Israel. IEJ, 8, 52–65.

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1960). The Mosaic Floor of the Synagogue at Ma'on (Nirim). In N. Avigad (Ed.), Eretz-Israel, Vol. VI, (The Mordechai Narkiss Book) (pp. 86–93). Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society. (Hebrew)

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1962). The Mosaic Floor of the Beit Alfa Synagogue and its Place in Jewish Art. In The Executive Committee (Ed.), The Beit She'an Valley, The Seventeenth National Convention for the Study of the Land of Israel (pp. 70–36). Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society. (Hebrew)

- Bagatti, B. (1955-56). Scavo di un Monastero al "Dominus Flevit". LA, VI, 240–270, Fig. 1–16, Pl. I.

- Balty, J. (1977). Mosaiques Antiques de Syrie. Brussel: Centre Belge de Recherches Archeologiques a Apamee de Syrie.

- Blanchard-Lemee, M., Ennaifer, M., Slim, H., & Slim, L. (1995). Mosaics of Roman Africa, Floor Mosaics from Tunisia. New York: Braziller.

- Bowersock, G. W. (2006). Mosaics as History, the Near East from Late Antiquity to Islam. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Caneva, G., Savo, V., & Kumbaric, A. (2014). Notes on Economic Plants Big Messages in Small Details: Nature in Roman Archaeology. Economic Botany, XX(X), 1–7.

- Celsus, A. C. (1938-1971). De Medicina, with an English translation by W.G. Spencer. London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Cimok, F. (Ed.). (2000). A Corpus, Antioch Mosaics. Istanbul: A Turizm Yayinlary.

- Cohen, R. (1980). The Marvelous Mosaics of Kissufim. BAR, 6(1), 16–23.

- Columella, L. J. M. (1954-1955). De Re Rustica, English Translation: Vol. I (Books 1-4) by H. B. Ash; Vols. 2 and 3 (Books 5-12 and the de Arboribus) by E. S. Forster and E. Heffner. London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Coombes, A. (2004). Pocket Nature Trees. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited.

- Dalby, A. (2003). Food in the Ancient World from A to Z. London, New York: Routledge.

- Danin, A. (1990). The Sycamore is not a Wild Tree. Teva Va'aretz, 325. Retrieved 2012.4.2 from http://www1.snunit.k12.il/heb_journals/aretz/325028.html (Hebrew)

- Dauphin, C. (1979). A Roman villa at Khirbet Susiya, near Hebron. IEJ, 29, 149–167.

- Dothan, M. (1968). The Synagogues in Hammath Tiberias. Qadmoniot, I(4), 123–132. (Hebrew)

- Dunbabin, K. M. D. (1999). Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Felix, J. (1967). Crossbreeding and Grafting, Tractate Kilayim, Mishnah Tosefta and Yerushalmi to Chapters 1-2, Clarification of the Issues and their Botanical-Agricultural Background with 188 Images and Schematics, Research Series. (Bar-Ilan University). Tel Aviv: Dvir. (Hebrew)

- Felix, J. (1991). Fruit Trees of All Kinds, Plants of the Bible and Talmud. Ramat Gan: Reuven Mass. (Hebrew)

- Felix, J. (2000). Jerusalem Talmud, Tractate Shevi'it. Jerusalem: Reuven Mass. (Hebrew)

- FitzGerald, G. M. (1931). Excavations at Beth-Shan in 1930. PEQ, 59–68.

- Foerster, G. (1985). The Zodiac in Ancient Synagogues and its Iconographic Sources. In N. Avigad (Ed.), Eretz-Israel, Vol. XVIII (The Nahman Avigad Book) (pp. 380–391, Plate 75). Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society. (Hebrew)

- Galen. (2003). On the Properties of Foodstuffs (De alimentorum facultatibus), Introduction, Translation, and Commentary by O. Powell, With a Foreword by John Wilkins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ganor, A., Klein, A., Avner, R., & Zissu, B. (2011). Excavations at Khirbet Madras in the Judean Shephelah 2011-2012: First Report. In E. David (Ed.), Innovations in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and its Surroundings, Vol. V (pp. 200–214). Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem Region. (Hebrew)

- Hachlili, R. (1987). 'A Book on the Problem of the Mosaicists of the School of Michael Avi-Yonah' (pp. 46–58). In D. Barag (Ed.), Eretz-Israel, Vol. XIX. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society. (Hebrew)

- Hachlili, R. (2009). Ancient Mosaic Pavements. Boston: Brill.

- Hirschfeld, Y. (2002). Deir Qala'a and the Monasteries of Western Samaria. In Y. Ben-Arieh & A. Reiner (Eds.), And This to Judah, Studies in the History of the Land of Israel and its Settlement Presented to Yehuda Ben-Porat (pp. 209–249). Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi. (Hebrew)

- Hyams, E. (1971). Plants in the Service of Man, 10,000 Years of Domestication. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company.

- Janick, J., Paris, H. S., & Parrish, D. C. (2007). The Cucurbits of Mediterranean Antiquity: Identification of Taxa from Ancient Images and Descriptions. AoB, 100, 1441–1457.

- Celsus, A. C. (1938-1971). De Medicina, with an English translation by W.G. Spencer. London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Columella, L. J. M. (1954-1955). De Re Rustica, English Translation: Vol. I (Books 1-4) by H. B. Ash; Vols. 2 and 3 (Books 5-12 and the de Arboribus) by E. S. Forster and E. Heffner. London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Galen. (2003). On the Properties of Foodstuffs (De alimentorum facultatibus), Introduction, Translation, and Commentary by O. Powell, With a Foreword by John Wilkins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lafaye, G. (1892). Mosaique de Saint-Romain-En-Gal (Rhone). Revue Archéologique, Tome XIX, 322–347.

- Magen, Y. (1993). The Samaritan Synagogue at Khirbet Samara. The Israel Museum Journal, XI, 59–64.

- Magen, Y. (2008). The Samaritans and the Good Samaritan. Jerusalem: Staff Officer of Archaeology – Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria.

- Ovadiah, R., & Ovadiah, A. (1987). Mosaic Pavements in Israel: Hellenistic, Roman, and Early Byzantine. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Patrich, J., & Tsafrir, Y. (1993). A Byzantine Church Complex at Horvat Beit Loya. In Y. Tsafrir (Ed.), Ancient Churches Revealed (pp. 265–272). Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Piccirillo, M. (1993). The Mosaics of Jordan. Amman: American Center of Oriental Research.

- Pliny, the Elder. (1949-1962). The Natural History, with an English Translation in Ten Volumes by Rackham H. London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Richmond, E. T. (1936). Basilica of the Nativity. The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine, V, 75–81, Pls. XXXVII-XLVIII.

- Safrai, Z. (2010). Agriculture and Farming. In C. Hezser (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Daily Life in Roman Palestine (pp. 246–263). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stern, H. (1981). Les Calendriers Romains Illustres. In H. Temporini (Ed.), Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der neueren Forschung, Band II, 12.2 (pp. 431–475). Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

- Talgam, R., & Weiss, Z. (2004). The Mosaics of the House of Dionysos at Sepphoris. Qedem, 44.

- Theophrastus, E. (1961). Enquiry into Plants and Minor Works on Odours and Weather Signs, with English Translation by Sur Arthur Hort, Bart, M.A. London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Trilling, J. (1989). The Soul of the Empire. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 43, 27–72.

- Tzaferis, V. (1983). The Excavations of Kursi – Gergesa. Atiqot, XVI, 1–64, Pls. I-XIX.

- Varro, M. T. (1934). On Agriculture, English translation by W. D. Hooper and H. B. Ash. England: Loeb Classical Library.

- Vincent, L. H. (1901). Une Mosaique Byzantine a Jerusalem. Revue Biblique, X, 436–444.

- Vincent, L. H. (1922). Une Villa Greco-Romaine a Beit Djebrin. Revue Biblique, XXXI, 259–281.

- Weiss, Z. (2005). The Sepphoris Synagogue: Deciphering an Ancient Message through its Archaeological and Socio-Historical Contexts. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Weiss, Z., & Talgam, R. (2002). The Nile Festival Building and its Mosaics: Mythological Representations in Early Byzantine Sepphoris. In J. H. Humphrey (Ed.), The Roman and Byzantine Near East, Vol. 3 (pp. 55–90). Ann Arbor, MI.: University of Michigan.

- White, K. D. (1967). Agricultural Implements of the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zohary, D., Hopf, M., & Weiss, E. (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World, Fourth Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Abbreviations

- BAR – Biblical Archaeology Review

- DOP – Dumbarton Oaks Papers

- IEJ – Israel Exploration Journal

- LA – Liber Annuus, Studii Bablici Franciscani

- PEQ – Palestine Exploration Quarterly

- QDAP – The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine

- RA – Revue Archéologique

- RB – Revue Biblique

- השוואת השכרת רכב: לחצו להשוואות השכרת רכב המשתלמות ביותר

- השוואת מלונות: לחצו להשוואת מלונות הכי שווים במחירים הכי משתלמים

- השוואת טיסות: לחצו להשוואת טיסות הכי משתלמות

- מוניות: מצאו מונית מנמל תעופה אל המלון במחיר הכי משתלם

- כרטיסים לאתרים ואטרקציות: מצאו כרטיסים לאתרים ואטרקציות במחירים הטובים ביותר

דברו איתנו וקבלו הצעת מחיר וייעוץ מקצועי לטיול הבא שלכם בארץ או בחו"ל