אביטל ענת, 2015, 'העיטור בפרחי שושן צחור באומנות היהודית של תקופת הבית השני', מורשת ישראל, כתב-עת ליהדות לציונות ולארץ ישראל, אוניברסיטת אריאל בשומרון, 12, עמ' 41-52

Avital, Anat. (2015). "The Decoration of Madonna Lily Flowers in Jewish Art of the Second Temple Period" , Moreshet Israel, Journal for Judaism, Zionism, and the Land of Israel, Ariel University in Samaria, 12, pp. 41-52.

Download:

2015, העיטור בפרחי שושן צחור באומנות היהודית של תקופת הבית השני', מורשת ישראל, כ'ע ליהדות לציונות ולארץ ישראל, אוניברסיטת אריאל בשומרון, 12, עמ 41-52.1

The Decoration of Madonna Lily Flowers in Jewish Art of the Second Temple Period (Translated From Hebrew)

Summary

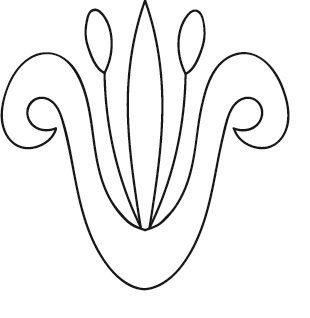

Many designs of lily flower (Madonna lily; French: Fleur de lis) were common in the Jewish art of the Second Temple period. The various models have basic structure of profiled flower cup consisting of two symmetrical bent out leaves, while the central leaf is upright. This primary model sometimes stylized by scrolled out leaves, added stamens, stems and rosettes of leaves. The model absorbed inspiration from several parallel artistic sources: Assyrian, Phoenician, Egyptian, Hellenistic and Roman, some ancient and some of the Second Temple period, for example, Palmette, Nymphaea and the lightning of Zeus. These foreign models were received into the Jewish art after adaptation process, while avoiding pagan symbols and while translated into a white lily flower, the beautiful large local flower. Those adaptations took place while keeping the decorative and symbolic power of the models. The model assimilated as a favorite motif in Jewish art and was identifiable with the lily flower, Lilium L. Candidum, geophyte who belongs to the Liliaceae family. Realistic design of the model shows the direct connection of the model makers with the surrounding nature, scrupulous observation of flora and the exact copy of morphological details. Nonetheless, the artists show adherence to acceptable fashion models, trendy decoration patterns and style.

Avital, Anat. (2015). "The Decoration of Madonna Lily Flowers in Jewish Art of the Second Temple Period", Moreshet Israel, Journal for Judaism, Zionism, and the Land of Israel, Ariel University in Samaria, 12, pp. 41-52.

The Decoration of Madonna Lily Flowers in Jewish Art of the Second Temple Period

Avital, Anat. (2015). "The Decoration of Madonna Lily Flowers in Jewish Art of the Second Temple Period", Moreshet Israel, Journal for Judaism, Zionism, and the Land of Israel, Ariel University in Samaria, 12, pp. 41-52.

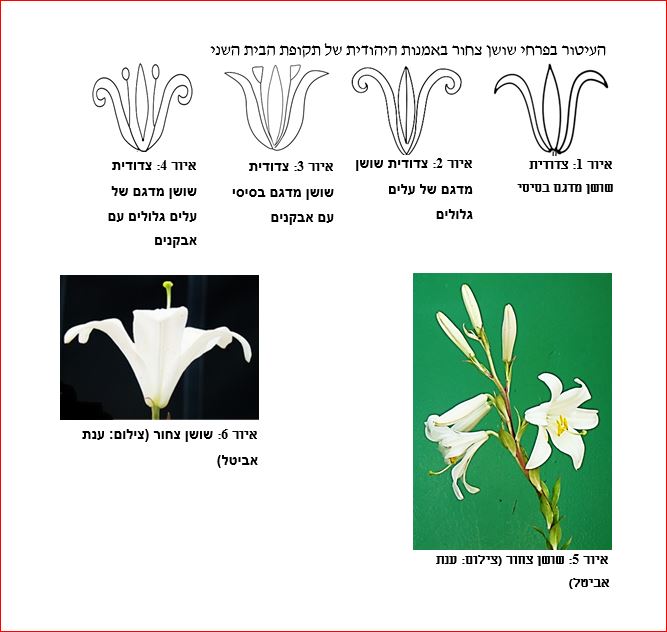

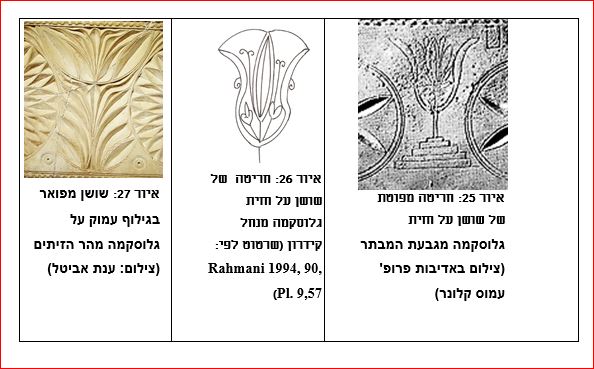

Many designs of the Madonna lily (Lilium candidum) are widespread in Jewish art from the Second Temple period. These designs generally have a basic structure of a symmetrical flower cup, composed of two slightly outward-curled petals, with an upright leaf in the central part of the cup (Figure 1). This basic lily design served as the foundation for the development of diverse patterns, some simple and schematic, and others more developed, stylized, and intricate. Sometimes, the flower was stylized with outward-curled petals, and stamens, stems, and lily leaves were added (Figures 2, 3, 4). This paper surveys some of the sources and transformations of the lily motif until it became established in Jewish art as a favored motif, with its realistic design that can be identified with the Madonna lily, L. Lilium Candidum, a geophyte in the Liliaceae family.

The symmetrical, beautiful lily design with three petals drew inspiration from several parallel artistic sources: Assyrian, Phoenician, Egyptian, Hellenistic, and Roman, some from earlier periods and some from the Second Temple period itself. The origins of these early designs are based on depictions of flowers or leaves, some of which are only partially identifiable. The attractive lily design is easy to decorate, well-suited to filling spaces, and its appeal has endured throughout the ages.

Imported motifs were assimilated into local art through a long process of adaptation to social and religious concepts, and became established in Israel only after the design was associated with the appearance of a locally recognized plant. After the symmetrical design from external sources was adopted and integrated into Jewish art, original and realistic lily designs developed, indicating that the creators of these designs used living, fresh Madonna lilies as models. It is believed that during the Second Temple period, the Madonna lily was relatively common in ornamental gardens in the Jerusalem area, since most scholars agree that the Madonna lily did not grow naturally in the Jerusalem region, and it is unlikely that it could have been brought to Jerusalem from afar before it began to fade (Felix 1968, 238; Danin 2014; Rahmani 1994, 50-51). The direct and unmediated connection of the designers with the surrounding nature, their careful observation of plants, and the accurate reproduction of morphological details are evident in the art of the Roman and Byzantine periods, both in Israel and beyond (Avital 2014; Rahmani 1994, 48-51; Caneva et al. 2014).

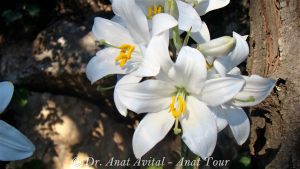

The beauty of the structure of Madonna lilies, their symmetry, and the size of their flowers made them very popular. The Madonna lily is white and fragrant, with the flower’s cup reaching up to 10 cm in length. Its shape is like a funnel that opens outward, composed of tepals with a prominent vein running along their length (Figures 5, 6). The flower features high stamens and a long style; the stigma is large, spherical to triangular. The upright, non-branched stem grows up to 150 cm in height, bearing numerous sword-shaped leaves that decrease in size as they rise; the lower leaves are the largest, resembling lily petals (Ze'iri 1982, 605-604; Levana, 1993, 211). The habitat of the Madonna lily is limestone cliffs, and its origin is unclear. Some believe it originated in Turkey (Lavelle 2006, 112), where it was domesticated in the mid-second millennium BCE (Horovitz & Danin, 1983, 85). The plant spread to the Near East and around the Mediterranean, becoming very common in northern Israel and Lebanon. During the Roman period, due to their beauty and pleasant fragrance, the flowers were harvested by the local population for decorative purposes. The bulbs were dug up and used to make medicinal balms for healing wounds, and the Madonna lily was cultivated as an ornamental plant. Later, the Madonna lily was adopted by Christianity as a symbol of modesty and was harvested for decorating altars. Plants were also transferred to monastery gardens. Today, small clusters of Madonna lilies remain in Israel, especially in the Carmel and Galilee regions, growing on cliffs and in hidden corners that humans have not reached (Felix, 1968, 238; Horovitz & Danin, 1983, 85 Tl. IV, 90).

Several features of the lily’s appearance identify it with the symmetrical flower motif: the symmetrically rounded flower cup at the base, the slightly outward-curling tepals, high stamens, and a prominent style rising above the tepals. The central upright leaf reflects the flower's appearance when viewed from the side, with a prominent vein running along the tepals and developing buds alongside the open flowers.

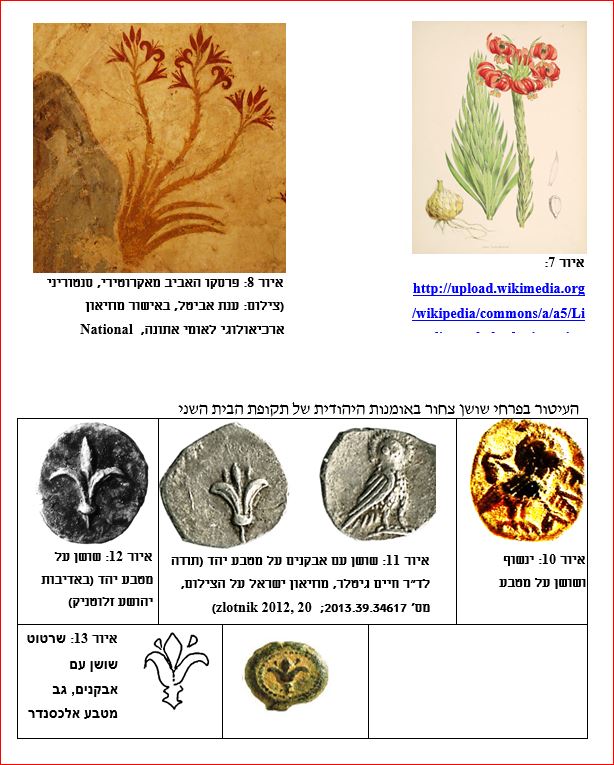

The decorative value of Madonna lilies has been recognized since antiquity. Realistic and stunningly beautiful depictions of red lilies, which can be identified with a species common in Greece and the Aegean islands, L. chalcedonicum (Figure 7) (Horovitz & Danin, 1983, 89; http://www.panoramio.com/photo/38119935, accessed 18.1.2014), were already designed in wall paintings from the ancient Minoan culture of Akrotiri on the island of Santorini (Thera), dating to the period before the volcanic eruption in the 16th century BCE (Figure 8) (Zafiropoulou 2009, 14-15). Additional red lilies were also depicted on the "Prince of Lilies" wall painting from the palace of Knossos, Heraklion (http://magendavidalbum.blogspot.co.il/2010/10/12.html, accessed 26.01.2014). Madonna lilies appear in wall paintings from five sites in Pompeii from the Roman period, integrated into plant designs of ornamental gardens (Jashemski and Meyer, 2002, 121).

The Establishment of the Lily Motif in Jewish Art

The entry of the Madonna lily motif into the decorative repertoire of Jewish art during the Second Temple period began hesitantly and modestly, around 360-399 BCE. It first appeared as a small flower with three petals depicted next to an owl on Yehud coins of the "imitated Athenian coinage" type. At this stage, the lily on the Yehud coins replaced the olive branch motif from Athenian coins, likely due to the association of the olive branch with the goddess Athena and its pagan connotations, which were problematic for Jews (Figure 10) (Saraga 2011, 54; Meshorer 1997, 17-16, 171, 253 Plate 3, Coin 6b). Later, the lily motif became more prominent and openly adopted on Yehud coins that replaced their predecessors, with a full lily design covering the entire surface of the coin. This lily design typically featured three petals, with two high stamens between them, and the reverse of the coin depicted an owl (Figure 11). Sometimes, the flower was depicted without the stamens (Figure 12) (Meshorer 1997, 173; 254 Plate 2, 15; Goldman 1977; Zlotnik 2012). Similar designs also adorned Hasmonean coins (Figure 13) (Meshorer 1997, 186, 281 Plate 29 P4; Zlotnik 2011).

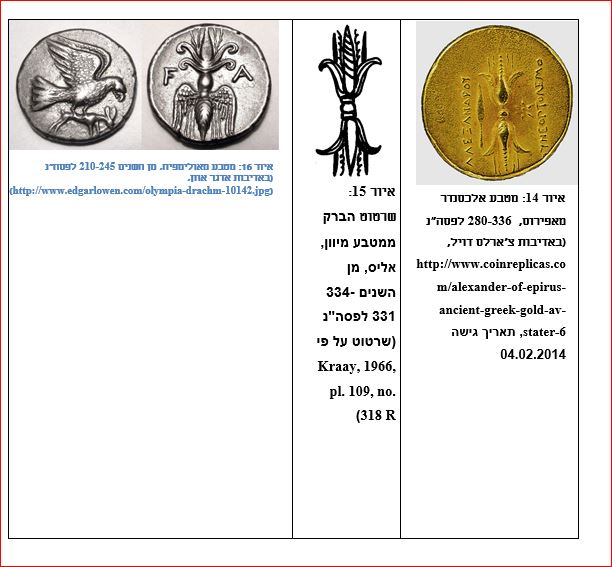

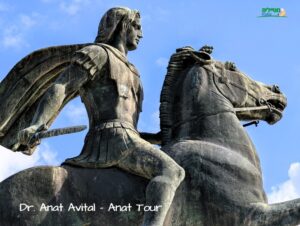

It is interesting to highlight the significant similarity between these lily designs and two heraldic elements that form the thunderbolt (Latin: fulmen; English: Thunderbolt), Zeus's powerful weapon, depicted on the reverse of Hellenistic coins from the 5th to the 2nd centuries BCE (Figures 14, 15) (Kraay, 1966, Pl.159, No. 499; Pl. 109, No. 318; http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/greece/elis/olympia/t.html, accessed 15.2.2014). The thunderbolt symbol consists of two similar heraldic elements, held together by a triangular ring. One element consists of two wings representing southern winds, and the other represents flames. Between the wings and the flames, spears or tridents – straight, spiraling, or twisting – are depicted, simulating showers of rain. All these components are clearly illustrated on Hellenistic coins (Figure 15), and are explained by Virgil:

"A load of pointless thunder now there lies

Before their hands, to ripen for the skies:

These darts, for angry Jove, they daily cast;

Consumed on mortals with prodigious waste.

Three rays of writhed rain, of fire three more,

Of winged southern winds and cloudy store" (Virgilius, Book VIII, p. 177).

The power of the thunderbolt and its association with the absolute rule of the king of the gods, as well as its role as his weapon, are indisputable. It seems that the Jews adopted half of this symbol, adapting it into a neutral, vegetal form, with the intent of avoiding pagan symbols. At the same time, they cleverly succeeded in preserving the markers of power and authority embodied in the design, and managed to maintain the fashionable appeal of the coins, ensuring their acceptance in the monetary market (Meshorer, 1997, 16). It is possible that after the adaptation of the thunderbolt to the local mentality, the lily flower still had the capacity to convey a sense of political power, and it became established in Jewish art as a symbol of the independent Kingdom of Jerusalem or as a symbol of the priesthood (Meshorer, 1994, 18-17; Zlotnik, 2008; Rahmani, 1994, 51).

During this period, the Jews freely used motifs borrowed from other peoples, including foreign and pagan motifs presented on Yehud coins, some of which were not even modified or filtered in their adaptation to Jewish coins. For example, predatory birds on Yehud coins with lilies, the "god in a chariot," portraits, owls, the goddess Athena, and eagles (Meshorer, 1997, 16, 256-253, Plates 4-1). Even during the Hasmonean and early Roman periods, the trend of adapting pagan symbols to floral designs continued. For example, the caduceus of Hermes was replaced by a pomegranate, with the adoption of certain symbols such as the cornucopia on coins of John Hyrcanus (Meshorer, 1997, 38-37, 268 Plate 16, and 12) and Herod’s coins (Meshorer, 1997, 297 Plate 45, 59h).

Today, it is difficult to determine whether the lily motif was initially adopted with the intention of representing the Madonna lily from the start, or if this representation is a modern interpretation, retroactively attributed to the lily after the motif's adaptation and establishment in the later Second Temple period, with its meaning and development into a realistic lily design.

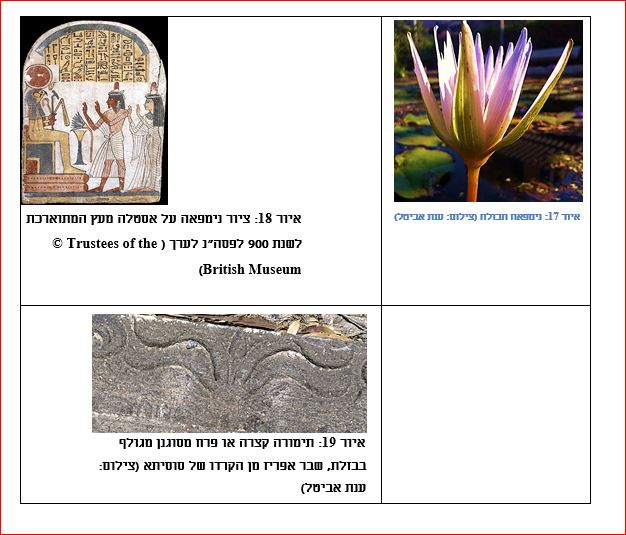

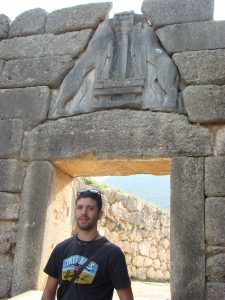

As mentioned, the design of the lily in Jewish art of the Second Temple period drew inspiration both from floral motifs and from flower designs in surrounding art, with these influences forming its foundation. Thus, it seems that the lily cup imitates the two lower leaves of the palmette, merging the upper leaves into a single upright leaf (Shiloh, 1979), and sometimes it also abstracts the palmette, using only its upper part (Zafiropoulou, 2009, 31, 71-76). For example, in a basalt carving from Susita, the flower is a short palmette or a flower with two cups (Figure 19). Regarding the connection between the palmette and the lily, there is a widely accepted chain of hypotheses that relies on circular reasoning and leads to a logical fallacy: a. It is assumed that the Madonna lily (Lilium candidum) is identified with the architectural capital motif, referred to in the Bible as "the work of the lily" (1 Kings 7:19) (Felix, 1968, 236-234); b. It is assumed that the Proto-Aeolic capital from the First Temple period can be identified with the 'work of the lily' mentioned; c. It is concluded that the lily designs on Yehud coins and the lily designs in Jewish art of the Second Temple period were inspired by the Proto-Aeolic capital and represent a continuation of the Jewish tradition from the First Temple period of decorating with the Madonna lily (Meshorer, 1997, 18-17).

Contrary to this circular reasoning, which cannot be proven, the Proto-Aeolic capital was rejected by Yigal Shiloh as the source for the lily designs in Jewish art of the Second Temple period, as its origins are different. He thoroughly demonstrated that the Proto-Aeolic capital design developed as a representation of the date palm tree, influenced by the palmette motif. He showed that the artistic origins of the Proto-Aeolic capital come from Western Asia and the northern Levant, areas where the date palm had symbolic value from the third millennium BCE until the beginning of the first millennium BCE; in his view, the tree represented the Asherah in Canaanite-Phoenician worship (Shiloh, 1979, 26-49). According to Shiloh, there is no botanical connection between the Madonna lily and the Proto-Aeolic capital design; however, it is proposed here that there is a formal influence of the palmette on the lily design.

The lily design also imitates flowers depicted on the "Tree of Life" from Assyrian ivory carvings from the eighth century BCE (http://studentreader.com/nimrud-ivories/; Ziso 2014). The design was also influenced by nymphaea motifs (Figure 17) sculpted in stone and painted in Egyptian art, such as a painting on a wooden stele dating to approximately 900 BCE (Figure 18) and ivory carvings on ceramic vessels from Cyprus from the seventh century BCE (Kyriakou, 1996, 55-56). The lily design was also influenced by depictions of lilies in reliefs on Roman-period ceramic amphorae dated to the second century BCE (Kyriakou, 1996, 99).

Many designs of symmetrical flower cups, whether singular or in rows, were very fashionable in Roman art of the second and first centuries BCE, used for decorating vessels, wall paintings, and stone carvings. In keeping with the fashion of decoration across the Roman Empire, Jews also designed similar flower cup motifs. Most of these designs were schematic, patterned, and similar to one another, yet many were created with original designs and integrated into unique compositions. Pediments of tombs were decorated with floral designs, including lily motifs. For example, in the façade of the Jehoshaphat Cave (Avigad, 1954, 135, Figure 77), on mezuzahs, and at the base of the entrance lintel of the Ashkelon Cave (Kloner and Ziso, 2003, 276-273), as well as in stylized lily carvings, such as the relief on a stone fragment from the Temple Mount (Figure 20).

Many façades of ossuaries were decorated with a variety of lily motifs, many of which were uniquely designed, stylized, intricate, creative, and even realistic. Small lily flowers were often used to decorate the corners left for decoration or the angles of ossuaries, and lilies were also incorporated into 'running' patterns to create borders or decorative strips (Rahmani 1994, 214, Pl. 93, No. 643). In contrast, large lily flowers were generally placed in the center of the façade, between two rosettes. The rectangular shape of the ossuary façade dictated uniform rules for decoration: an outline frame, with the majority of the rectangular space filled by two parallel rosette circles. Between the two rosettes, a space resembling two inverted cones (hourglass shape) was left, which was filled with designs whose spatial shape matched. Various models of vessels, architectural designs, and diverse floral motifs completely filled the available space, for example, an amphora or a jar, a triangular base with a column, a stepped architectural base with a column or stem and a flower at the top, a base with lily leaves and a stem topped by a large lily, two inverted flowers connected by a column or stem, and other variations, all designed to fill the space shaped like the two inverted cones (Rahmani 1994, 32-51).

The base design of the lily was schematically carved or deeply engraved on the ossuaries (Figure 21), in various original designs (Rahmani 1994, 214 Pl. 3 No. 643; 155 Pl. 49 No. 341; 214 Pl. 93 No. 643). This basic design evolved into more complex models through the addition of tepals, stamens, buds, tepals, stylistic elements, or a realistic appearance. The developments were made according to the budget which determined the artist's level of skill and the extent of investment in carving and engraving work, as well as the size of the space to be filled.

Two opposing flowers with numerous petals filled the space between the large rosettes on the façade of an ossuary from the family of Caiaphas, with each flower having two lateral tepals and a single upright central leaf (Figure 22; Greenhut 1992, 113). In other cases, a single flower with numerous petals was designed only on the upper cone (Rahmani 1994, 104, Pl. 15, No. 105).

In the center of several ossuaries, a complete lily plant with a stylized flower was designed. For example, in the center of the façade of an ossuary from Dominus Flevit, a plant was carved, showing five lily leaves at the base. From the center of the leaves, a twisted stem rises, bearing a lily flower, with delicate twisted branches and tiny buds emerging from between the lily leaves (Figure 23). Sometimes, between the tepals, two stamens also rise (Figure 24; Rahmani 1994, 123, Pl. 26, No. 195; 247-248, Pl. 121, No. 816:F).

The Realistic Lily in Jewish Art

Several unique lily designs, featuring many realistic details, represent the peak of artistic development of the motif and demonstrate a direct connection of the creators with the plant in its blooming form. In a shallow engraving on the façade of a tomb from Giv'at HaMivtar, a staircase is depicted, with a large flower cup supported by a stem. The cup holds a flower with three petals, two prominent stamens, and at the base, a lily-like arrangement of leaves (Figure 27) (Kloner, 1972). The external cup likely represents a cup-shaped vessel, frequently depicted on Jewish tombs, or it could be the beginning of the depiction of the outer parts of the lily. The internal part, however, is an original creation by the artist, including almost all the components of the lily flower: lily petals, tepals, and stamens.

Another shallow engraving from a tomb in Kidron Valley depicts a cup that imitates fashionable designs of flowers between rosettes, or it might be the beginning of a lily flower cup. In the center of the cup, a large bud is depicted, with two tepals and two stamens on either side (Rahmani 1994, 90, Pl. 9,57) (Figure 26). In a deeply and impressively carved piece from the Mount of Olives tomb, a sophisticated and ornate lily design is prominently featured at the top of a stem adorned with leaves. The internal parts of the flower, the stamens, and the style are clearly and intentionally designed (Figure 27).

Conclusion

The lily design in Jewish art was influenced by several designs prevalent in the art of the period and earlier periods: the palmette, Assyrian flower motifs, the nymphaea, and the thunderbolt of Zeus. These designs entered Jewish art after a process of adaptation for the local population, while maintaining original design features: the structure of the flower cup and the upright central leaf. In this way, the Jews preserved the symbolic power of the thunderbolt and used floral symbols from Assyrian, Egyptian, and Greek art, while cleverly avoiding pagan symbols. The design was translated by Jewish artists into the Madonna lily, the large and beautiful local flower, in a process of translation and adaptation that allowed the motif to enter Jewish art in an acceptable form, while preserving its symbolic and decorative power.

A large variety of lily designs appear in Jewish art from the Second Temple period on coins, tomb façades, ossuaries, and oil lamps. The simplest designs are schematic, and sometimes only hint at the lily decoration. In contrast, more developed and realistic designs clearly depict the full components of the plant and flower, making it possible to identify them botanically as the Madonna lily. The large variety of lily designs indicates direct observation of the living flower and an artistic desire for creativity and originality. However, there is also a strong adherence to fashionable and accepted designs, with decoration following similar patterns and consistent style.

Abbreviations

Danin 2014 – Written information from Professor Avinoam Danin, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Ziso 2014 – Written information from Professor Boaz Ziso, Bar-Ilan University.

Caneva 2014 – Written information from Professor Julia Caneva, Third University of Rome.

Hebrew Bibliography

Avigad, N. (1980). The Upper City of Jerusalem. Jerusalem.

Avigad, N. (1954). Ancient Tombstones in the Kidron Valley. Jerusalem.

Avital, A. (2014, unpublished). Agricultural Crops and Tools in Mosaics from the Late Roman and Byzantine Periods in Israel, PhD thesis, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan.

Bilig, Y. (1995). "Jerusalem, Arnona", Archaeological News, 70-71.

Goldman, Z. (1977). "The Symbol of the Madonna Lily: Its Origin, Meaning, and History in Antiquity", in Yearbook for Biblical and Jewish Studies, 11, Jerusalem, 197-221. (http://magendavidalbum.blogspot.co.il/2010/10/blog-post_2499.html, accessed 21.7.2014).

Greenhut, C. (1992). "The Tomb of the Kifa Family in North Talpiot, Jerusalem", Antiquities, 25(3-4), 111-114.

Greenhut, C. (2012). "Jerusalemite in Jerusalem – The Assault of a City in the Light of Its Past", Dvar Avra, 17: 13-15. (http://www.antiquities.org.il/pdf/lagaat/may2012.pdf, accessed 26.01.2014).

Ze'iri, M. (1982). All the World’s Plants, Jerusalem.

Zussman, W. (1972). Decorated Oil Lamps, Jerusalem.

Zlotnik, Y. (2008). "Landmarks in Hasmonean Minting Authority", https://www.academia.edu/780923/Landmarks_in_Hasmoneans_Minting_Authority_Hebrew.

Levana, M. (1993). "Madonna Lily", in: The Flora and Fauna of Israel, A Practical Illustrated Encyclopedia, Alon, Azaria (Ed.), Volume 11, Rishon Lezion: 209-211.

Meshorer, Y. (1994). A Treasury of Jewish Coins, Jerusalem.

Faz, A. (1988, A). "Is the Madonna Lily White? (A)", Nature and Land, 8, 17-22.

Faz, A. (1988, B). "Is the Madonna Lily White? (B)", Nature and Land, 9, 14-19.

Felix, Y. (1968). The Biblical Flora, Ramat Gan-Givatayim.

Kindler, A. (1986). "Agricultural and Floral Models on Jewish Coins in Israel", in: Man and Land in Ancient Israel, Oppenheimer, A. and colleagues (Eds.), Jerusalem: 223-230.

Kloner, A. (1972). "A Second Temple Period Tomb in Givat Hamivtar, Jerusalem", Antiquities, 5, 108-110.

Kloner, A. & Ziso, B. (2003). The City of Tombs in Jerusalem during the Second Temple Period, Jerusalem.

Rahmani, L.Y. (1977). Design of the Decoration of Jewish Ossuaries in the Form of Tombs in Jerusalem, PhD Thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Foreign Bibliography Caneva G., Savo V., & Kumbaric A., 2014, 'Notes on Economic Plants Big Messages in Small Details: Nature in Roman Archaeology', Economic Botany, XX(X): 1-7.

Goodenough E.R., 1953, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period. I. New York and Toronto.

Horovitz A. & Danin A., 1983, 'Relatives of Ornamental Plants in the Flora of Israel', Israel Journal of Botany, Vol. 32: 75-95.

Jashemski W.F., & Meyer F.G. (Eds.), 2002, The Natural History of Pompeii, Cambridge.

Kraay C.M., 1966, Greek Coins, New York.

Kyriakou G.P, 1996, Cyprus Heritage, the Art of Ancient Cyprus as Exhibited at the Cyprus Museum, Limassol.

Lavelle M., 2006, The World Encyclopedia of Wild Flowers and Flora, London.

Rahmani L.Y., 1994, A Catalogue of Jewish Ossuaries, Jerusalem.

Reifenberg A., 1937, Denkmaeler der Juedischen Antike, Berlin.

Saraga N., 2011, The Stoa of Attalos, the Museum of the Ancient Agora, Voskaki, A. (Ed.), Athens.

Shiloh Y., 1979, The Proto-Aeolic Capital and Israelite Ashlar Masonry, Qedem 11, Jerusalem.

Zafiropoulou D., (Ed.), 2009, The National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Zlotnik Y., 2011, 'Alexander Jannaeus’ coins and their dates', https://www.academia.edu/663697/Alexander_Jannaeus_coins_and_their_dates_English _, 05.02.2014.

Zlotnik Y., 2012, Minting of coins in Jerusalem during the Persian and Hellenistic periods, https://www.academia.edu/5517837/Minting_of_coinage_in_Jerusalem

_during_the_Persian_and_Hellenistc_periods_English_, 04.02.2014.

חוחן ארץ ישראלי פריחת קיץ סגולה וקוצנית

שום תל אביבי: פריחת אביב בשרון לאורך מישור החוף

אדמונית החורש: פרח ורוד-ארגמן אביבי

סחלב פרפרני: פריחה אביבית סגולה-ורודה

דרדר גדול-פרחים: פריחת קיץ סגולה

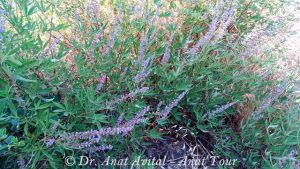

מרוות ירושלים: פריחה סגולה בחורף ובאביב

כליל החורש: העץ שכולו פורח בוורוד זוהר באביב

שיח אברהם מצוי: פריחת קיץ סגולה בנחלי המים המתוקים ישראל

שמשון הדור: פריחה ורודה מפתיעה באביב בנגב ובדרום הארץ

מרווה צמירה: פריחה חורפית סגולה

חיננית הבתה – פרח לבן ורדרד וצהוב במרכז – פריחת חורף יפיפיה

דודא רפואי פריחת חורף סגולה, צמח רפואה

בן חצב סתווני: פריחה סגולה צנועה בסתיו

עדעד כחול: פריחת אביב וקיץ ברצועת החוף בישראל

חוטמית זיפנית: פריחת אביב ורודה על עמוד פריחה גבוה

סתוונית היורה: פריחת סתיו ורודה

עירית גדולה: פריחת חורף ים תיכונית בצבע לבן-ורוד

איריס נצרתי בשמורת אירוס נצרתי בהר יונה בנצרת

חבלבל השיח: פריחת קיץ ורודה

מרווה משולשת – פריחה ורודה של צמח התה וטיהור הגוף המושלם

חוטמית עין הפרה: פריחה ורודה באביב

קורטם מכחיל: קוץ, פורח בקיץ בסגול בצפון ובבקעת הירדן

גדילן מצוי צמח קוצני עם פריחה סגולה באביב

פריחת עשנן צפוף בחורף ובאביב

מרוות יהודה: עמודי פריחה סגולה באביב

חלמית גדולה: פריחת אביב ורודה באזורים ים תיכוניים

לשון פר סמורה: פריחת חורף סגולה-כחולה (או מופע לבן)

טיול שנתי לטיולי קבוצות ובתי ספר בארץ: מסלולי טיול בגולן ובגליל

חסה כחולת פרחים: פריחה תכולה באביב

לוטם מרווני ולוטם שעיר: פריחה בוורוד ובלבן באביב הישראלי

פריחת אירוס שחום בתקוע: טיול פריחה לתחילת האביב

אדמונית החורש: פרח ורוד-ארגמן אביבי

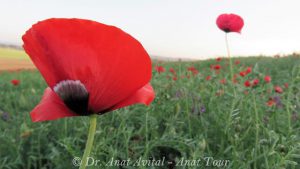

נורית אסיה: פריחת אביב אדומה מהצפון ועד לדרום

פרג נחות: פרג אדום קטן שפורח במישור החוף ובספר המדבר

פרג אגסי (אגסני): טיולי פריחה אדומים באביב

חומעה ורודה: פריחה אדומה-ורודה במדבר

טיול שנתי לטיולי קבוצות ובתי ספר בארץ: מסלולי טיול בגולן ובגליל

דמומית קטנת פרי: פרח אדום אביבי קטן ומקסים

חסה כחולת פרחים: פריחה תכולה באביב

צמרורת בואסייה: פריחת אביב בצבע תכלת יפיפיה בספר המדבר

דרדר כחול: פריחת אביב כחולה מהממת

איריס נצרתי בשמורת אירוס נצרתי בהר יונה בנצרת

עדעד כחול: פריחת אביב וקיץ ברצועת החוף בישראל

לשון פר סמורה: פריחת חורף סגולה-כחולה (או מופע לבן)

ליבנה רפואי: עץ עם פריחת אביב לבנה וריחנית

חרוב מצוי: עץ ים-תיכוני חובב חום

יסמין שיחני: שיח די נדיר עם פריחת אביב צהובה

אלון מצוי: עץ ירוק עד בחורש הים תיכוני

משקפיים מצויים: פריחה צהובה בחורף בצפון

ערבה מחודדת: עץ על פלגי מים, נחלים ומעיינות

פריחת חלמוניות בסתיו בחניון להבים בנגב – בחודש נובמבר מדי שנה

דלעת-נחש מצויה: פריחת חורף ואביב בצבע צהוב

לוטוס מכסיף: פריחת אביב וקיץ לאורך מישור החוף

פריחת קדד באר שבע: פריחת חורף מדברית בנגב

אספרג החורש: מתי ואיפה מוצאים, ומתי אפשר לאכול ממנו?

בקיית הכילאיים: פריחת אביב בכל האזורים הים תיכוניים

פריחת חרצית עטורה: המלכה הצהובה של האביב הישראלי

זוטה לבנה טעם וריח מנטה עדין ומשובח לתה צמחים

חיננית הבתה – פרח לבן ורדרד וצהוב במרכז – פריחת חורף יפיפיה

לשון פר סמורה: פריחת חורף סגולה-כחולה (או מופע לבן)

פריחת שושן צחור: מלך פרחי האביב הישראלי בחודש אפריל

ליבנה רפואי: עץ עם פריחת אביב לבנה וריחנית

דלעת-נחש מצויה: פריחת חורף ואביב בצבע צהוב

גזר קיפח: תפרחת לבנה גדולה וגבוהה- באביב ובקיץ

רותם המדבר: פריחת חורף לבנה עם ריח מטריף חושים

עירית גדולה: פריחת חורף ים תיכונית בצבע לבן-ורוד

חבצלת החוף: מלכת הפרחים הלבנה והרייחנית של סוף הקיץ ותחילת הסתיו

פריחת חצבים – חצב מצוי- כשהקיץ בורח והחצב פורח

נץ החלב ההררי- פריחת חורף לבנה

אספרג החורש: מתי ואיפה מוצאים, ומתי אפשר לאכול ממנו?

עוזרר קוצני: עץ קטן בחורש הישראלי עם פרחים לבנים באביב

ערבה מחודדת: עץ על פלגי מים, נחלים ומעיינות

לוטם מרווני ולוטם שעיר: פריחה בוורוד ובלבן באביב הישראלי

כליל החורש: העץ שכולו פורח בוורוד זוהר באביב

פיקוס השקמה: גמזיות מתוקות על עץ עתיק ומיוחד מאוד

אלון מצוי: עץ ירוק עד בחורש הים תיכוני

רותם המדבר: פריחת חורף לבנה עם ריח מטריף חושים

עוזרר קוצני: עץ קטן בחורש הישראלי עם פרחים לבנים באביב

נחל כלח בשוויצריה הקטנה: טיול קצר מהיפים בכרמל

ערבה מחודדת: עץ על פלגי מים, נחלים ומעיינות

ליבנה רפואי: עץ עם פריחת אביב לבנה וריחנית

חרוב מצוי: עץ ים-תיכוני חובב חום

אלה אטלנטית: עץ נשיר גדול, עם עפצים בצורת אלמוגים

רותם המדבר: פריחת חורף לבנה עם ריח מטריף חושים

דודא רפואי פריחת חורף סגולה, צמח רפואה

פיקוס השקמה: גמזיות מתוקות על עץ עתיק ומיוחד מאוד

אספרג החורש: מתי ואיפה מוצאים, ומתי אפשר לאכול ממנו?

סתוונית היורה: פריחת סתיו ורודה

עירית גדולה: פריחת חורף ים תיכונית בצבע לבן-ורוד

גדילן מצוי צמח קוצני עם פריחה סגולה באביב

חומעה ורודה: פריחה אדומה-ורודה במדבר

פריחת חרצית עטורה: המלכה הצהובה של האביב הישראלי

זוטה לבנה טעם וריח מנטה עדין ומשובח לתה צמחים

יסמין שיחני: שיח די נדיר עם פריחת אביב צהובה

מרווה משולשת – פריחה ורודה של צמח התה וטיהור הגוף המושלם

גזר קיפח: תפרחת לבנה גדולה וגבוהה- באביב ובקיץ

עוזרר קוצני: עץ קטן בחורש הישראלי עם פרחים לבנים באביב

חרוב מצוי: עץ ים-תיכוני חובב חום

כליל החורש: העץ שכולו פורח בוורוד זוהר באביב

טיול באתונה: מדריך מלא למטיילים באתונה, 10 האתרים היפים באמת

טיול VIP עם הדרכה פרטית בגיאורגיה ליעל ולנכדתה היקרה | אוקטובר 2022

חלמית בפריחת קיץ בפירינאים Malva moschata

ברלין בירת גרמניה: טיול באירופה הקלסית

אצבעונית ארגמנית – Digitalis purpurea – Foxglove

אורן שחור Pinus uncinata

שדר כסוף – ליבנה כסוף Silver Birch

אשוח כסוף- Silver Fir- Abies alba

דלפי ביוון: עירם של האורקל ומקדש אפולו- מדריך מלא למטייל

אגם קולומרס – פארק אייגואסטורטס, הפירינאים הספרדיים

ד"ר ענת אביטל – מדריכת טיולים בכירה, חוקרת פסיפסים מהתקופות הרומית והביזנטית, ומרצה בתחומי טבע וארכאולוגיה.

בעלת מומחיות רבת־שנים, ניסיון של למעלה מ־30 שנה בהובלת קבוצות וייעוץ אישי למטיילים עצמאיים ו־ VIP בארץ ובעולם.

Dr. Anat Avital

Senior tour guide, mosaic researcher, and passionate storyteller with over 30 years of experience.

Specializing in tailor-made tours and VIP travel planning across Israel and worldwide.

Combining deep academic knowledge with warm, personal guidance – for travelers who seek meaning, depth, and unforgettable journeys.